A very special type of rock

If this is what a geologist would say of a small piece of typical sarsen, what would a witch doctor caveman? Have a read…

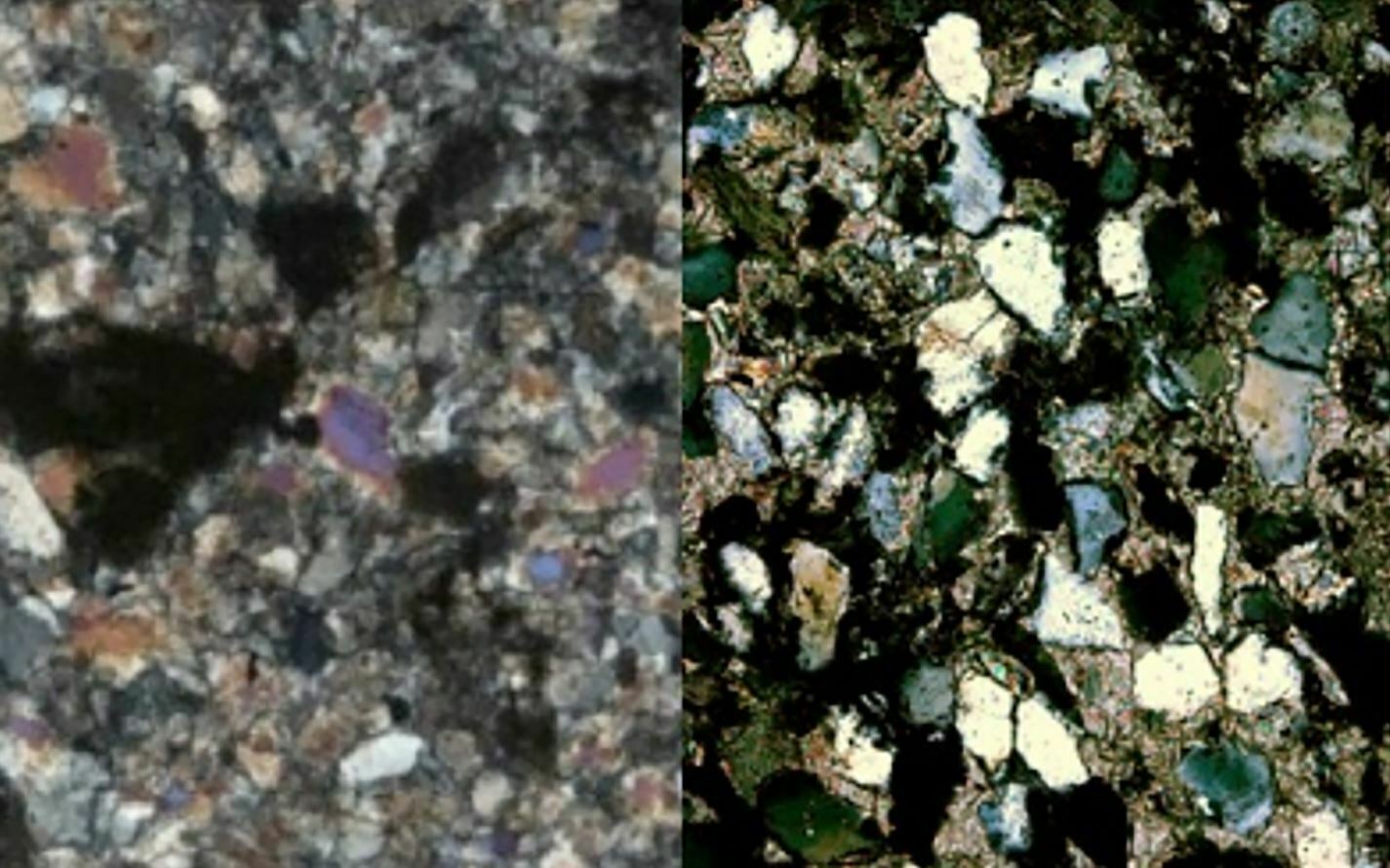

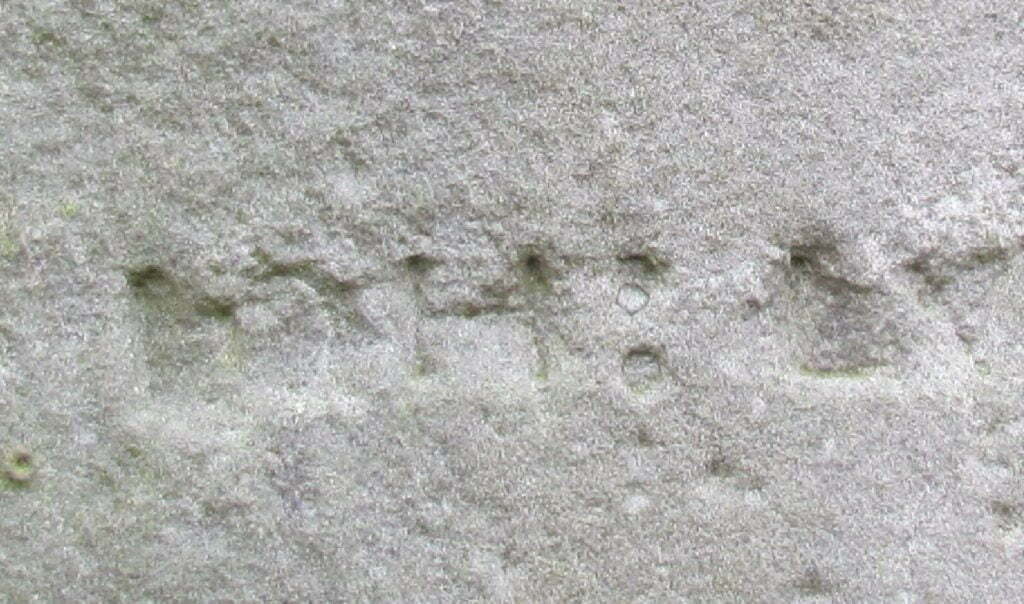

Macroscopically the sarsen is a greyish-red, indurated, fine-grained, unbedded, sandstone. Microscopically the rock is a vuggy, locally grain-supported quartz arenite comprising single, sub-rounded to sub-angular, detrital quartz grains with authigenic overgrowths and euhedral terminations growing into void spaces. Locally fine-grained hematite pigment or fine-grained, quartz mosaics overgrow and cement euhedral quartz. Rare, detrital, accessory minerals include green-brown tourmaline, oxidised chromite, red-orange rutile and zircon. Rock clasts are also uncommon but include rounded, chert/flint, a little metamorphic quartz, vein quartz and clasts carrying a very fine-grained hematite pigment.

In the Wiltshire Archaeological & Natural History Magazine, vol. 103 (2010), pp. 1-15

The petrography, affinity and provenance of lithics from the Cursus Field, Stonehenge

by Rob A. Ixer and Richard E. Bevins

Not withstanding that it is a typical geologist jargon-filled scientific description, impenetrable, unless you decipher nearly every word, slowly. I like the rust in the quartz veins. Just a touch of colour… And those void spaces filled with crystals! And, bits of older, dumped, larger crystals: tourmaline, chromite, rutile and zircon. And, get this… Bits of trees. Prehistoric palm tree root voids. Pudding stones. This is not a plain old sandstone

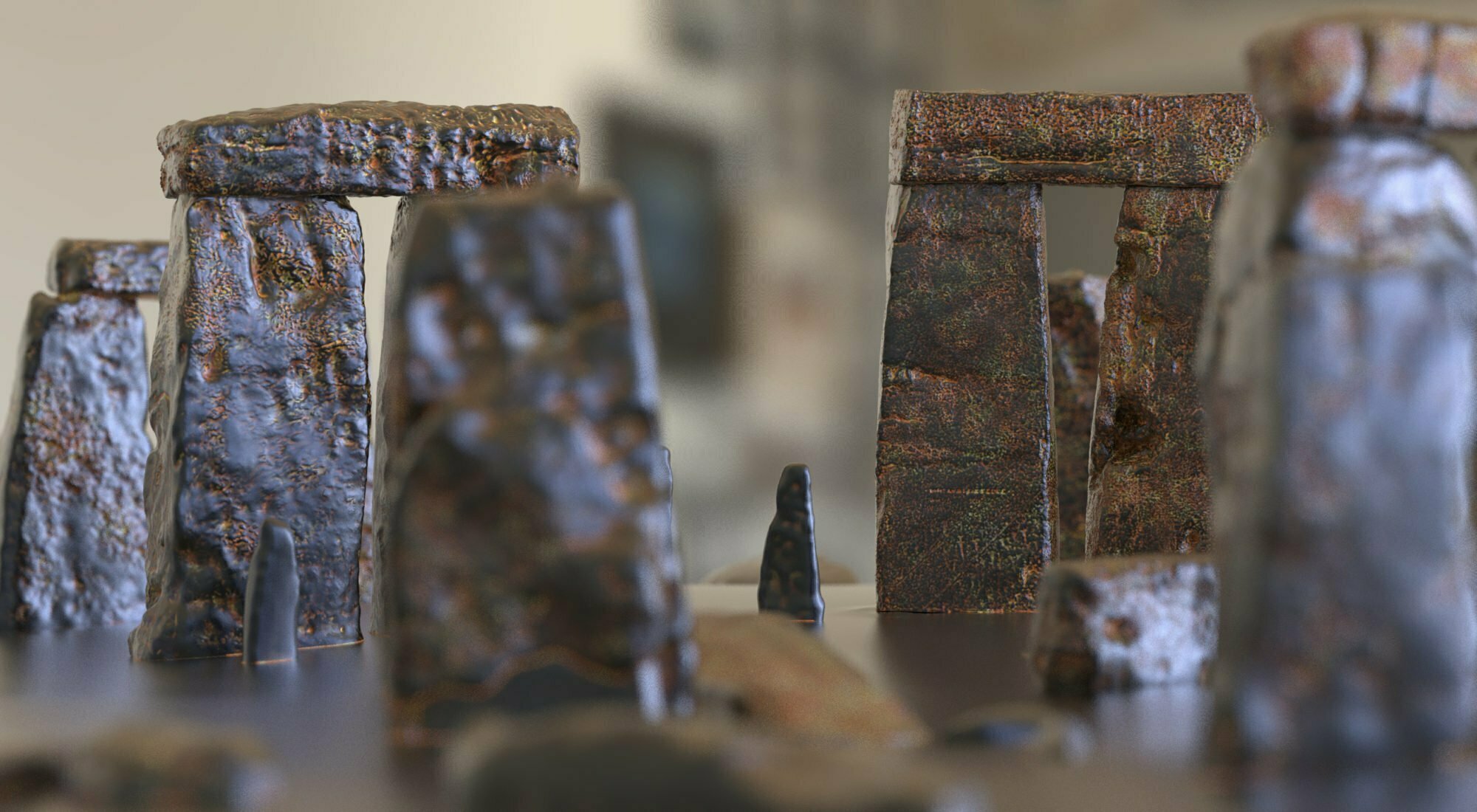

One special kind of rock. Better when polished up. Much better.

These are classic examples, but not from Stonehenge sarsens, just for an illustration of what colours could be found amongst the polished faces of such a rock as sarsen.

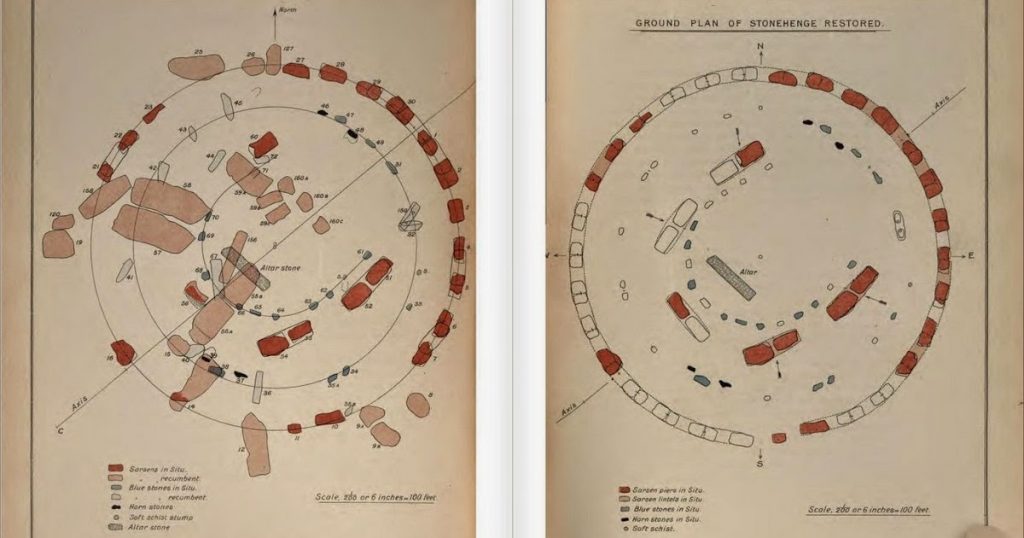

How many stones at Stonehenge?

53 sarsens remain from an estimated 85 at Stonehenge. The other, smaller stones are collectively called bluestones. There are 43 of these. 33 are above ground while a further 10 are stumps below ground. The excavated holes and various configurations suggest that there are a further 36 bluestones missing from the monument.

How was sarsen stone made?

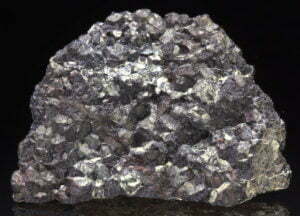

Sarsen is a type of hard silicified sandstone, maybe 60 million years old – certainly 30 million, Stonehenge's sarsen rocks have flint pebbles called pudding stones inside. Share on Xformed during the Lower Tertiary – that’s after the dinosaurs died out – as a once continuous crust over the chalk geologies of Southern England. Fine iron stained quartz sand and gravel, sometimes with flint grains and white feldspar, regularly containing flint pebbles called pudding stones.

What would the builders have understood by flint, something they found, on the ground (or later dug out of chalk pits) to be encapsulated in hard stone blocks laying, aligned over valleys?

Often fossil root holes can be seen in the stone, from millions of years ago when the stone was still forming, probably of prehistoric palms. Cementation was not uniform, surfaces were knobbly and pitted hollows and voids formed and were filled with iron-rich sands. Over time this rocky sand desert was swamped by silica-rich water, a sea or lake. It waxed and waned over eons crushing into sandstone with essentially quartz juice.

Broken up and slid around

More recently, the stone was eroded and broken up into large pieces and scattered over the English chalk downs and then, particularly in wet, periglacial times, the last ice ages, they were moved, in sarsen trains, down the valleys, lubricated by slippery, chalk, muddy streams.

The chalk of the London Basin is still capped by layers of this sandstone. A cap of Cenozoic silcretethat once covered much of southern England

Quartz is hard and it kills

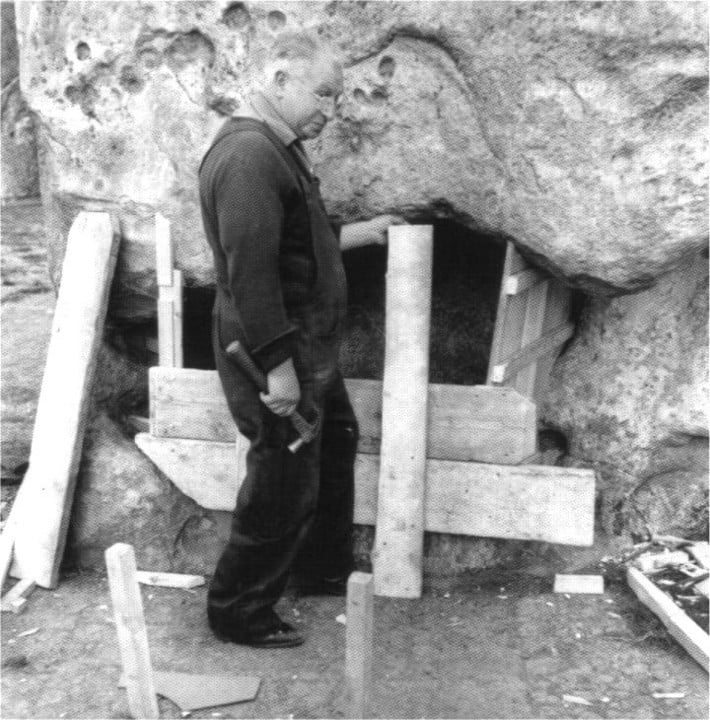

Sarsen is extremely hard being silicified but is easily crumbled when they have not been exposed to the atmosphere for very long. Suggesting that the dressing of the Stonehenge sarsens would have been easier when they were freshly uncovered. However, those vugs (or holes), the fractures, and veins would have made working the sarsens difficult and unpredictable. And to cap it all, there’s a disease called silicosis which a long-term lung disease caused by inhaling large amounts of crystalline silica dust, usually over many years.

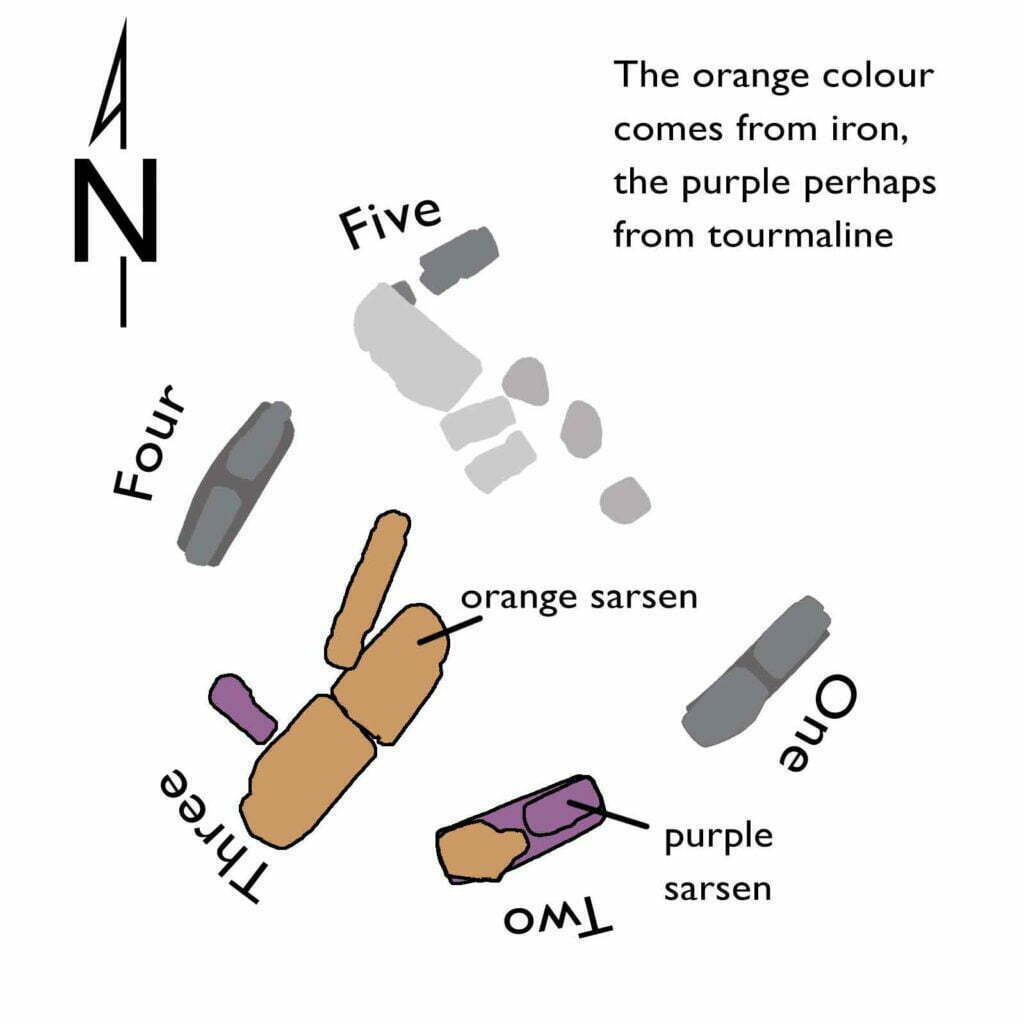

Sarsens are white to grey or yellow to orange. It depends on the mixture of minerals, iron makes them move towards orange. Different locations have different mineral makeups and thus different colours.

At Stonehenge Stones 53 (skinny) and 154 (lintel) are purple grey sarsen while 54 (fatty) is orange sarsen. However, Trilithon Three (the central trilithon of the horseshoe) is the opposite, having two orange: the fallen 55 (fatty) and the lintel 156 and one purple grey – the tallest stone, skinny Stone 56. If it wasn’t for the difference in height one could wonder if the Trilithons were mixed up.

They appear to sweat in damp weather when water condenses on their surface and make them look like giant lumps of coarse sugar.

No good for furniture. William Stukeley wrote that sarsen is “always moist and dewy in winter which proves damp and unwholesome, and rots the furniture”

Magic stones

Legend has it that they had the ability to breed underground. Farmers would say that there was no point removing them from fields as more would grow, that they would just appear and damage ploughs.

However, they were moved to the edges of fields and then reused in walls, gateposts and paving. They are often found built into the walls of churches and other important buildings. Often used as boundary markers, particularly by the Saxons, they are also used as markers in church graveyards. They have been broken up and used as macadam for roads. There are few left on Salisbury Plain, though there were once many.

Sarsen was used throughout Southern England and France

Sarsen have been used not only for Stonehenge but across Southern England, e.g. a barrow near Avebury; Wiltshire; a chambered tomb in Kent; a stone row in Portesham, Dorset; a long mound near Warminster, Somerset; a barrow near Littleton in Hampshire; a parapet wall of sarsens at Uffington Castle, Oxfordshire; even as far as a standing stone in Gennes, France.

Recent studies of the sarsens at Stonehenge have lead people to believe that the stones used were brought not solely from Marlborough Downs (some 30 miles northeast of Stonehenge) but from all across Southern England even as far east as Norfolk.

It’ll certainly be revealing to find the exact original locations not only Stonehenge but all the other monuments in Sothern England. Were they taken, given, or even bought from distant tribes? It has long been postulated that Stonehenge was built by one tribal leader. But perhaps it was several tribes bringing ‘rock offerings.’

Update: the origin of the sarsens has been found. The closest of several likely northern sites — West Woods. 25km as the crow flies and nearly all came from the same area. Yes, including the rough and undressed Heel Stone.

Older, smaller bluestone

The bluestones were definitely brought from many miles away, they appear to be from several locations in South Wales.

- Carn Menyn, Carn Alw, Carn Goedog and Craig Rhos-y-felin in the Preseli Hills in the Welsh county of Pembrokeshire.

- The Altar Stone (Stone 80) is a pale green micaceous sandstone likely from the Old Red Sandstone of the Senni Beds in the Brecon Beacons.

Recent thought postulates that the bluestones were assembled in Wales as a henge. And this happened some 500 years before Stonehenge. They were then brought to Stonehenge. This being so, it seems likely that the sarsens were also brought from further afield, too. Perhaps for the same reasons, trophies were taken by conquering armies, tributes, gifts or the unification of different tribes of Southern England or even migrations across the Southern Downs and further?

(More on the bluestones on another page… When I write it.)

Etymology

The word itself is thought to be a corruption of the medieval term for Muslim – Saracen which also came to mean alien or stranger or foreigner. Or it perhaps it was taken as pagan or heathen – from the use in ancient monuments – like Stonehenge. Or from sar-stan meaning troublesome stone.

It is also called greywether or graywether or druid-stone or druidical stone. ‘Wether’ being an Old English word for sheep. And there is a pair of prehistoric stone circles called The Grey Wethers in Dartmoor 100miles south-west of Stonehenge.